16 December 2020

In the summer of 2015, Yusra Mardini and her sister fled their hometown Damascus during the Syrian civil war. They embarked on what would turn out to be an arduous 25 day journey to Germany [1]. Their first stop was Beirut. They subsequently passed through Istanbul, and afterwards went to Izmir. In this coastal Turkish town, the sisters boarded a crampy boat to cross the Aegean Sea towards Lesbos. They were accompanied by twenty fellow travelers [2].

Shortly afterwards, disaster struck. The motor stopped and their vessel stalled. As most of the passengers were unable to swim, their lives were on the line. Luckily, Yusra – who was merely seventeen at the time – had been swimming professionally for years prior to the hazardous undertaking. Along with her sister Sara, she had competed in numerous junior competitions. Whereas in those instances a medal was the aim, the pernicious circumstances now demanded a completely different goal: reaching Lesbos’ shore.

They jumped into the water and started pulling the boat towards the coast. Propelled by their world-class swimming capabilities, Yusra and Sara managed to guide the boat to the Greek island safely after an intense journey of more than three hours on the open waters. More importantly, all passengers remained unscathed. The sisters’ efforts had proved vital to the successful completion of the journey towards Germany, which they eventually reached via Macedonia, Serbia, Hungary, and Austria.

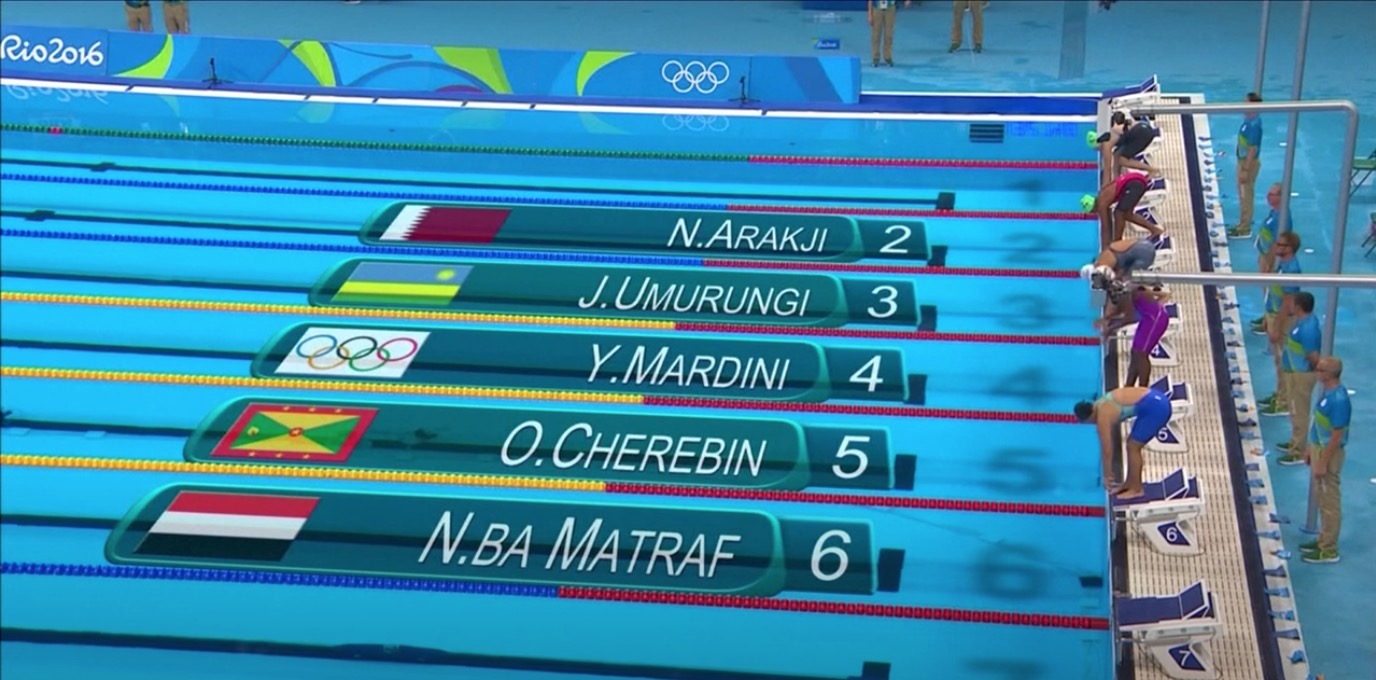

Fast forward a year. Having recovered on German soil, Yusra was able to focus on her career yet again. The readoption of her demanding training schedule and hard work resulted in a chance for her to compete in the Rio Olympics. Representing the Refugee Olympic Athletes’ team (as opposed to her home country, Syria) on August the 6th, she managed to win in her heat of the 100m butterfly. A roar erupted from the crowd, followed by a thundering applause. Although her time was not enough to qualify for the semi-finals, Yusra had won the approval and admiration of thousands of spectators.

Violence from within

Unfortunately, not all of Germany’s refugees are applauded. Although Merkel had instigated an “Open Arms” policy at the time, many Germans still viewed the newcomers with suspicion. Even more disconcertingly, refugees were often harassed and attacked.

In order to gain an accurate understanding of these attacks, the Amadeu Antonio Foundation and PRO ASYL (a human rights organization) have collected data on events during which asylum seekers were subject to abuse in one form or the other. Their data was collected and neatly formatted by the researchers David Benček and Julia Strasheim [4] [5]. The data points are divided into four main categories:

- Demonstrations. This is a type of social unrest that is deliberately targeted at refugees. They comprise xenophobic protests during which people voice their displeasure with the newcomers and Germany’s “Wir Schaffen Das” credo. A notable organization that fosters such demonstrations is Pegida. Sometimes, such protests have Nazi undertones. During a Pegida protest on 14 March 2015, at least one man was reported shouting “Sieg Heil!” [4].

- Assault. This type of attack concerns physical assaults and bodily injuries. During these attacks, refugees incur beatings and sometimes the pouring of hot liquid on their body, for which they need medical treatment.

- Arson. Such attacks are directed against refugee housing. The culprits aim at setting their temporary homes on fire.

- Other attacks. This category comprises different types of vandalism against (would-be) refugee housing, including xenophobic graffiti slogans and willful damaging.

The aforementioned dataset contains data for the years 2014 and 2015. After personal correspondence with Dr. Strasheim, she has sent me a larger dataset that also includes information for the years 2016 and 2017. For that, I am very thankful.

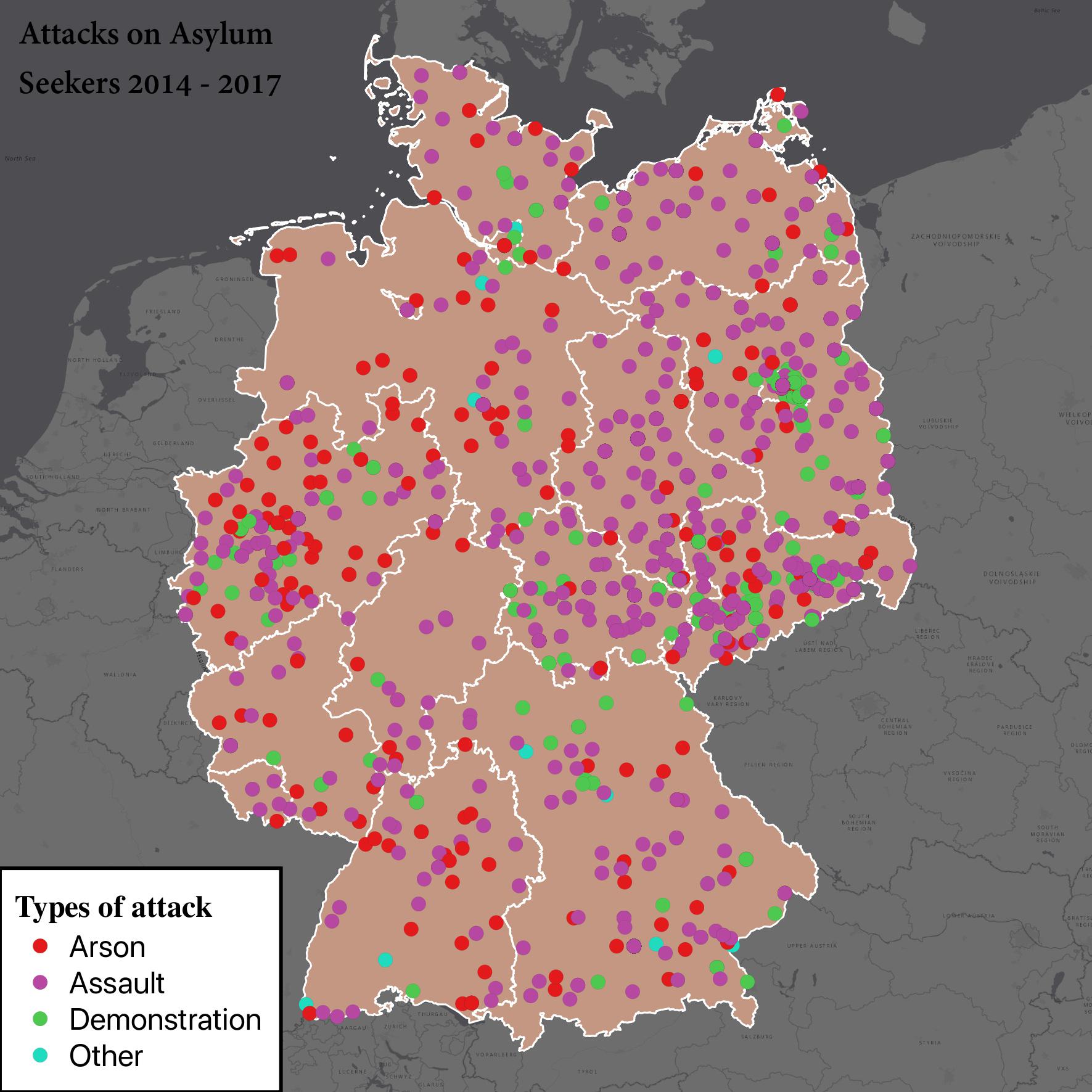

A first impression of these attacks is depicted in the following picture, in which I plotted them (2014 – 2017) by type with QGIS. Please note that I pruned that data points that were not categorized whatsoever. This is the result:

A number of observations can be made based on this map:

- First of all, the amount of attacks in the Assault category seems to be especially high in the Eastern part of the country;

- Second, instances of attacks in the Assault category appears to be the most prevalent among all types of attacks. It is followed by the Arson and Demonstration categories (not necessarily in that order). Other Attacks is clearly the smallest category.

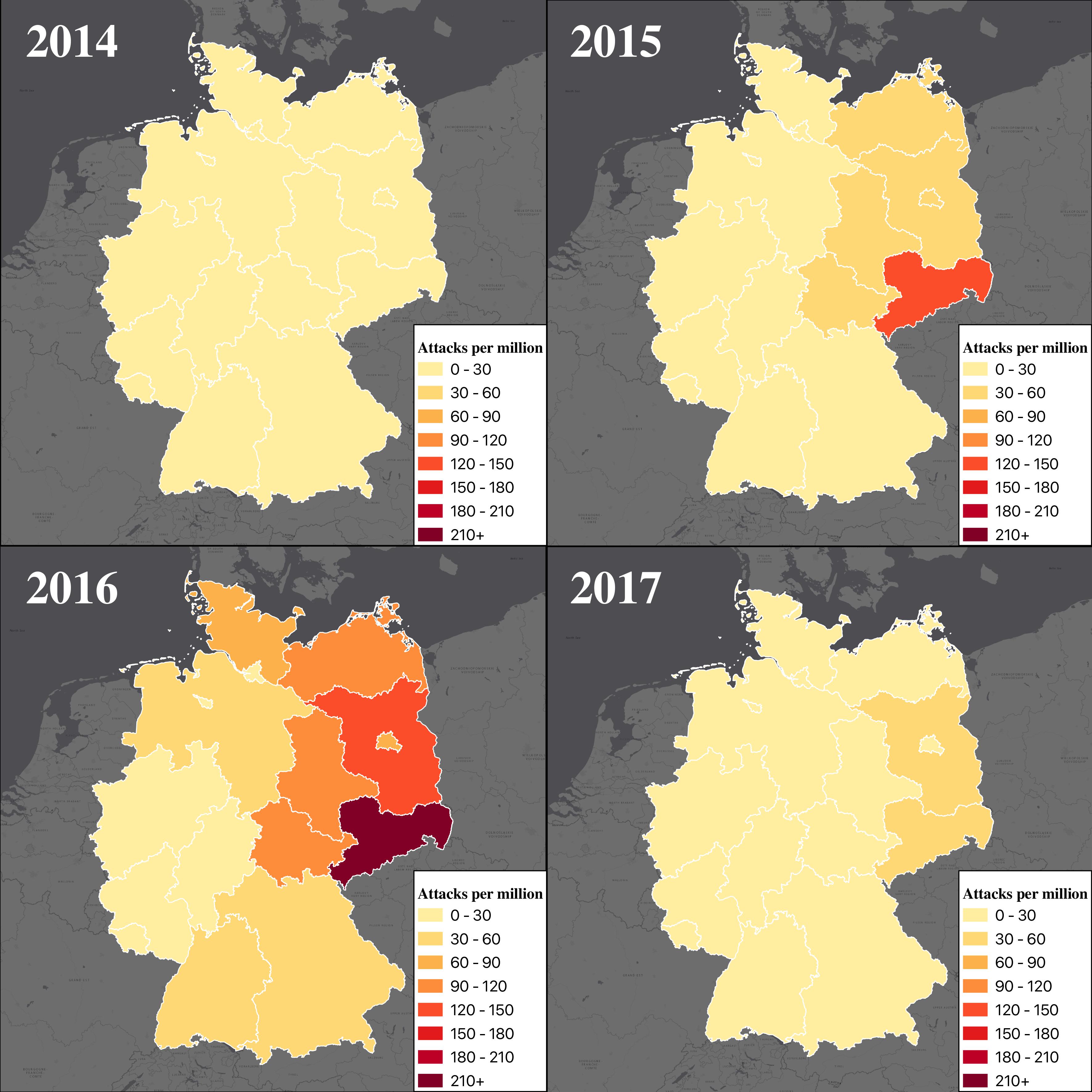

Although this is somewhat helpful, merely plotting the data may only allow for a small and incremental increase in our understanding of these ad hominems. The density of the attacks – the total amount of attacks per capita, that is – should provide a clearer picture. Here is the density of attacks depicted for the respective years:

These images provide even greater evidence of our initial suspicion that attacks on refugees are more commonplace towards the Eastern part of the country. In fact, they show that the more Eastward one goes, the more often refugees are attacked on a yearly basis. Only in the Westernmost part of Germany, the asylum seekers seem to remain relatively unscathed throughout the years.

Problems with violence targeted at refugees seem to have reached their peak in the year 2016. In the early months of that year, the asylum applicants in Germany have predominantly heralded from Syria (48% of arrivals). This roughly coincides with the course of the Syrian Civil war, which we mentioned in relation to the Mardini sisters’ journey. By 2015, the EU struggled to cope with the refugee crisis, which prompted European countries to seek multilateral agreements with countries including Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey to account for the housing of refugees in exchange for monetary donations. In 2016, a number of such agreements were reached.

We now return to the image above. It shows 2016 was the most heated year in terms of citizen-to-refugee violence. Although the densities clearly establish this, it might be even more illuminating to depict an interactive map. This can help those not calling Germany their homeland to identify the different German states and provide more accurate information on the amount of attacks.

I therefore made the following map with Leaflet and GADM. One can hoover over the states to learn more about the attack rates.

Xenophobic DDR

Attacks on refugees have on the whole been much more prevalent in Eastern Germany (DDR) than in its Western (BRD) counterpart. This has its roots in the Western/Eastern divide of the country between 1945 and 1990. This has had a host of consequences that pertain to this day. Studies show for instance that about 58% of the inhabitants of the BRD agree with the statement “religious practice for Muslims in Germany should be seriously limited”, while 75% endorse this assertion [6].

These phenomena are quite remarkable. Why is there such a disparity between the former states? A plausible answer is the higher unemployment rate in former East German areas. When younger people and women went to the West, the East was left with a pool of older men that nostalgically yearned for the DDR in its former glory era. There is even a term for this, called Ostalgie [7].

Sachsen in particular stands out in terms of attacks on Refugees. As mentioned before, there were approximately 256.1 attacks on refugees per million inhabitants in 2016. That is almost twice as many as the attack rate on the province with the second-highest attack rate: 142.5 attacks / million in Brandenburg.

Dresden is Sachsen’s capital. During the years of the DDR/BRD division, it was the only city that could not receive Western television. In popular jargon, it was often referred to as the Valley of the Oblivious. Even though only 1% of its inhabitants were Muslim by 2015 and comparatively few foreigners have lived in the DDR during the Cold War period, Dresden has been the stage of regular Pegida demonstration marches and almost daily arson attacks. The comparatively bad economic predicament the Eastern Germans have found themselves in after the reunification might have prompted them to seek for a relatively powerless group of scapegoats, and found them in the population of foreigners.

Finally, political education is a factor that might persuasively explain the difference. Eastern Germany deemed the fascist tendencies of the Third Reich to be a consequence of capitalism. Having resorted to socialism after the Second World War, GDR’s citizens therefore considered themselves cleansed from their xenophobic attitudes. The politicians regarded the populace as victims of the fascist leadership, not as possible perpetrators. Dissident views were largely suppressed by the autocratic government and its infamous secret police.

Whereas Eastern Germany thus did not partake in the whole debate about guilt, the Western Allies made sure this conversation was held at all levels of BRD’s society. It was reinforced by a massive reeducation program and the spread of ideas of intellectuals within a lively, democratic atmosphere that stressed critical thinking about the Nazi past and all practices that are associated with it, from communal singing and marching in groups to the racist ideology itself.

The free flow of ideas and emphasis on the evaluation on one’s own actions and deeply held beliefs in the West stood in stark contrast to the static, willful ignorance of the East. The contrasting approaches to post-war politics have had far-reaching consequences in terms of attitudes to and beliefs of foreign people to this day in Germany.

We should thus certainly not underestimate the power of political education as an antidote to xenophobic beliefs and practices.

Sources

[1] Jon Schuppe and Kelly Cobiella, How Yusra Mardini survived a 25 day trek from Syria and became an Olympian: https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/team-refugees/how-yusra-mardini-survived-25-day-trek-syria-became-olympian-n601946 , NBC News, 5 August 2016

[2] Philip Oltermann and Esther Addley, From Syria to Rio: Refugee Yusra Mardini targets Olympic swimming spot: https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2016/mar/18/syria-rio-refugee-yusra-mardini-olympic-swimming , The Guardian, 18 March 2016

[3] Medyascop, OLYMPICS RIO SWIMMING REFUGEE/ Yusra Mardini: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=My-1olseX1Q , Youtube, 8 August 2016

[4] David Benček and Julia Strasheim, Refugees welcome? A dataset on anti-refugee violence in Germany: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2053168016679590 , Sage Journals, Research and Politics 5 December 2016

[5] David Benček and Julia Strasheim, Replication Data for: Refugees Welcome? A dataset on anti-refugee violence in Germany: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/I2CZQY , Harvard Dataverse, 21 September 2016

[6] Heribert Adam, Xenophobia, Asylum Seekers, and Immigration Policies in Germany, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13537113.2015.1095528 , Routledge, Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 13 November 2015

[7] Dominic Boyer, Ostalgie and the Politics of the Future in Eastern Germany, https://profiles.rice.edu/sites/g/files/bxs3341/files/inline-files/Ostalgie.pdf , Public Culture, 2008